Behaviour Models - Staying on the Right Side of Action Curve

I am working my way through the book called Tiny Habits: Why Starting Small Makes Lasting Change Easy by B.J. Fogg. First section of the book talks about behavioural models and explains why certain behaviours and habits are incredibly easy to form, whilst others seem nearly impossible.

The section ends by encouraging the reader to teach the concepts to someone else, which helps solidify their own grasp of the material. I figured, “why not clarify the model by writing a blog post?”. Grab a cup of tea and let’s dive in.

Shaping Habits

Ever thought about why some habits are a breeze to pick up, but others are super tough? There’s a model that can shed some light on this. Take the simple act of brushing your teeth in the morning.

To make this habit stick, you need three things:

- A prompt or reminder to do it.

- The motivation to actually want to do it.

- The ability or skill to do it right.

In a nutshell, it’s like this:

Behaviour = Prompt + Motivation + Ability.

Prompt

Let’s start with the prompt. Without a prompt, the behaviour will most likely not materialise. What’s the typical prompt for brushing the teeth? In my case it’s as follows: “When I walk into the bathroom and look in the mirror, I am reminded to brush my teeth”.

Ability

Now that I have been prompted to brush my teeth, I need to be able to do it. How easy is it to brush my teeth? A piece of cake. There is a fully charged electric tooth brush in my bathroom with a timer and a number of settings that make the whole process effortless.

But what if it wasn’t that easy? Let’s consider situations where it might be harder to brush the teeth:

- Manual toothbrush

- Water supply issues

- Travelling

- Shared bathroom congestion

Motivation

Now let’s talk about the last component of this model - motivation. Without any motivation it would be completely pointless to brush my teeth. Hopefully most of us are motivated to brush our teeth so that we can look after our long term health and to maintain hygiene.

But when might someone not feel like brushing? Two examples come to my mind:

- Not understanding importance of dental hygiene. Think about parents nagging their kids to brush teeth every morning and before going in bed.

- Person living in a warzone with bombs falling down from the sky where survival is their primary concern.

Let’s Visualise This

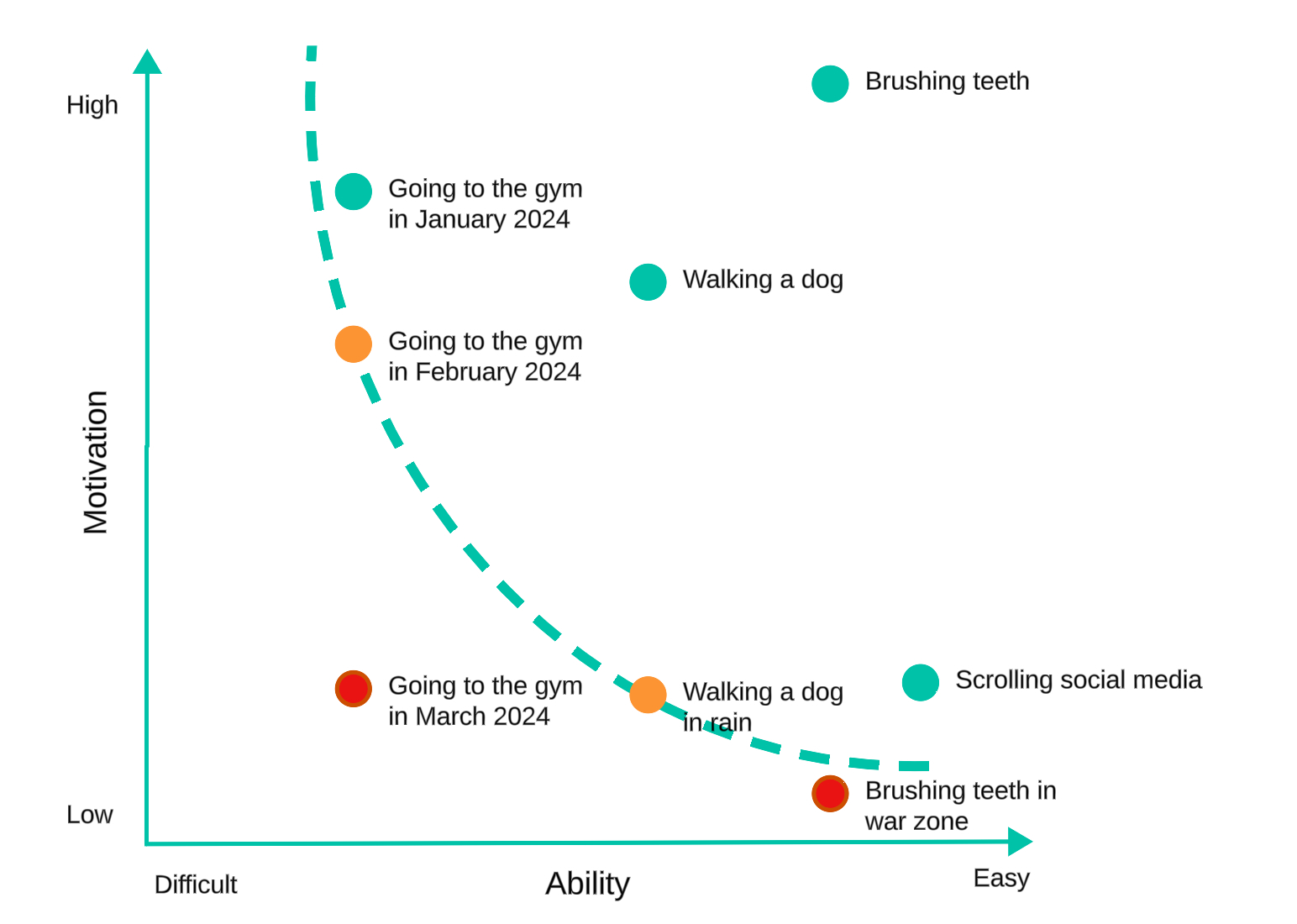

Now that we have a good idea of how this works, let’s plot a few of these behaviours on a graph and try to better understand why some turn into habits whilst other do not.

Green circles represent behaviours that are highly likely to occur. Orange circles cover behaviours that may not happen and red circles are for behaviours that will most likely not happen and therefore will not turn into habits.

- Example 1 - New Year Resolutions.

- In January 2024 you are super motivated to go to the gym. You are just about able to exercise and endure the pain, but you are flooded with motivation so you sign up and go to the gym.

- Comes February 2024 and your motivation has died down a little bit. Winter blues are kicking in and you start skipping a session here and there.

- March 2024 and your motivation is at ground zero. You cancel your gym membership. New habit isn’t formed.

- Example 2 - Walking the Dog.

- Assuming you love your dog (which is a requirement for reading this blog) and you find walking relatively easy, then a walking a dog is a behaviour that will most likely materialise.

- However, if it is raining outside and you still need to walk the dog, then your motivation might drop and odds of you not walking the dog might increase. That is unless you absolutely adore your dog (which you must do to be a decent human being), in which case your motivation will remain high and behaviour will come to fruition.

-

Example 3 - Last example is very relevant to current month of the year - January. This is a month where everybody makes new year resolutions and heads to the gym. Why is it that most people give up after a few months? Let’s plot this on the graph.

- Example 4 - Brushing Teeth.

- Brushing teeth. Highly motivated and very easy to do.

- Brushing teeth in a warzone. Whilst it might be easy to do, the motivation is probably non existent as survival is top priority. Habit is unlikely to form.

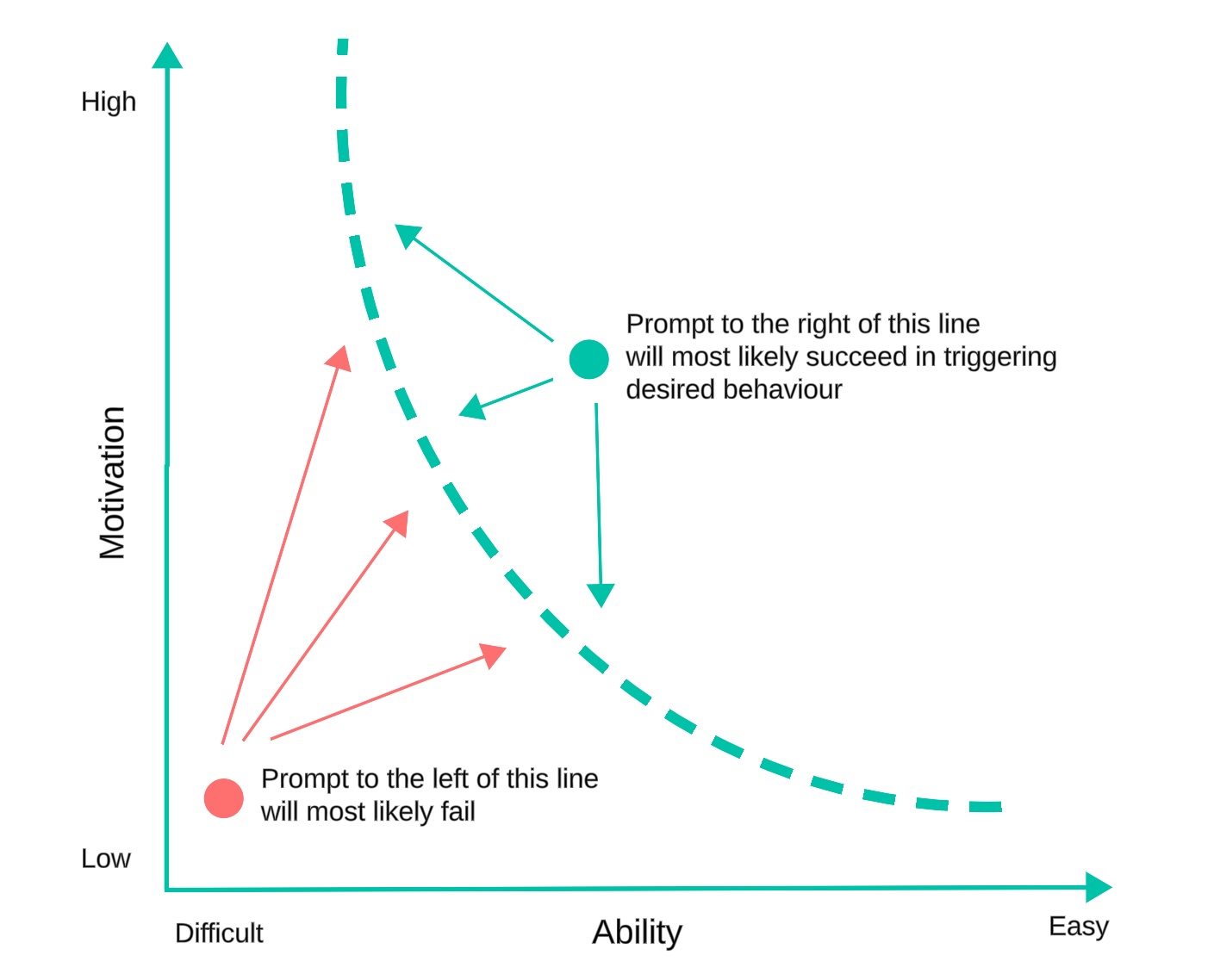

Stay on the Right Side

So what can I do with this knowledge? In brief, when there is a prompt and ability and motivation variables land you to the right of the dashed line, then you have a good chance of carrying out a set behaviour and eventually turning it into a desired habit. However, if your ability and motivation variables land you to the left of the line, then the odds of you forming a new habit are not good.

Closing Thoughts

What have we learnt? We learnt that behaviours don’t happen without prompt. When there is a prompt, there needs to be enough motivation and ability for behaviour to materialise. If this happens, then the odds are in your favour. If it doesn’t, then you are most likely to fail in forming new habit.

In the upcoming post I will show you how we can engineer habits and behaviours by tweaking motivation and ability variables to stay on the right side of the action curve. We will also look at how we can use existing prompts as anchors to formulate new good behaviours and drop less helpful ones.

Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson - What Did I Learn?

I just finished reading Elon Musk’s autobiography written by Walter Isaacson, the author of Steve Jobs’ autobiography, which I also read and thoroughly enjoyed a few years ago. I am not going to recap his life story in this post, but I will go over what I found to be most interesting.

Reality Distortion Field

Elon “suffers” from what some people refer to as a reality distortion field. He sets what many perceive to be totally unrealistic deadlines and targets. Surprisingly, these targets often create an optimal amount of pressure where people come together and deliver what previously seemed to be impossible. For example, relocating Twitter servers from one data center to another within days, as opposed to six months, thus saving millions in costs.

Requirements Origin

He continuously questions the origin of requirements to understand why they exist and what purpose they serve. It’s not enough of an answer to say that the requirement comes from a legal or infosec department.

You need to reach out to the person who made the requirement, talk to them, and then decide whether that requirement makes sense or not. Without questioning the norms, we risk becoming much slower, getting bogged down in unnecessary checks and controls instead of innovating and moving forward.

Mission Statement

His decisions are largely driven by his overarching mission: running six companies, each contributing directly towards his ultimate goal of becoming a multiplanetary species by colonizing Mars.

Why is it important to have a very clear mission statement? Because it helps you allocate your time and resources on what’s most important.

Key Performance Indicators

In order to deliver your mission, you must implement and track KPIs. For example, setting a KPI to build 5,000 Tesla cars per week meant that the company could become profitable by a certain date.

Another example is a KPI of driving down the cost of getting a payload to orbit. The industry average at the time was around $10,000 per kilogram of payload. Having and meeting a KPI of reducing that cost to under $3,000 ensures the company’s profitability and future growth.

Delete, Delete, Delete

It’s relatively easy to build something complex and over-engineered. Usually, the higher the complexity, the higher is the cost of build and maintenance. It’s much more difficult to build a solution that is both elegant and effective.

When faced with something incredibly expensive and complex, Elon questions all the norms and starts to delete components until he’s deleted so much that some need to be introduced back in. He refers to this approach as an “algorithm” and has successfully applied it at SpaceX and Tesla.

Fail Fast

Failure is where most learning takes place. Therefore, failure is good, but only as long as you can learn from it. Companies that are too risk-averse and never fail end up being too slow and ineffective in the long term. This is a core principle of the LEAN startup, yet many companies fail to adopt it and lag behind those that do. Some see a rocket blow up and call it a complete failure. Elon sees a rocket blow up and calls it a “rapid unscheduled disassembly” with lots of insights to learn from.

Hire and Keep 10x Engineers

Elon and his team let go of 90% of Twitter engineers by relying on the experience and judgment of their hardcore Tesla and SpaceX teams who have been with him for many years. Tesla AI (which is arguably a much more difficult problem to solve than a microblogging platform) only had a team of 150 engineers working on it when Twitter had a team in excess of 2000+ engineers.

If you want to be innovative and move fast, you must hire the best talent you can get. Unfortunately, many companies fail to accept the fact that it’s worth paying someone double the market rate as their productivity will be ten times that of an average engineer.

Don’t Tweet at Night

The more people depend on you and the more influential you are, the more considerate you need to be with what you say and how you say it. This is where Elon has continuously struggled throughout his life, partly due to his Asperger’s syndrome. At times, his outbursts brought good luck and fortune, but more often than not, he ended up rattling many feathers and losing billions in the process.

AlphaGo - Creative Approach to Winning in an Ancient Game of Go

I have recently watched an award-winning documentary called AlphaGo. It follows a team of Google’s DeepMind engineers who built a system to compete in an ancient game of Go. The documentary follows the DeepMind team as their AI model competes against, at the time, world Go champion - Lee Sedol. If you haven’t seen the documentary, I highly recommend watching it as it’s both incredibly interesting and insightful.

Five games were played with AlphaGo coming out victorious in four out of five matches - a shocking and rather upsetting result for the huge Go community.

The documentary left me with a range of emotions varying from amazement and excitement to sadness and anxiety. Moreover, it left me with three questions that kept bugging me:

- What is creativity?

- Is Alpha go creative?

- How do I feel about world’s best Go player losing to an AI model and how might this impact my hobbies and line of work in the future?

In this post I am going to explore these questions in some depth. I understand that whatever answers I will come up with, will be highly subjective, but it doesn’t mean I shouldn’t seek these answers. Let’s dive in.

Why Go?

Many of us have heard of a game called Chess, so let’s start by comparing Chess to Go. A game of Chess has a smaller board and multiple distinct pieces with different mechanics and rules surrounding them. Go, on other hand, has a much larger board, only one distinct piece per sice playing but a significantly higher number of possible moves.

| Chess | Go | |

|---|---|---|

| Board Size | 8x8 | 19x19 |

| Distinct pieces | 6 | 2 |

| Approximation of possible board positions | 10^50 | 10^170 |

Both games can be incredibly complex and the number of possible board positions can be unimaginable. Here’s some numbers for comparison:

- 10^13 is an approximate number of cells in a human body

- 10^27 is an approximate number of atoms in human body

- 10^69 is an approximate number of atoms in the Milky Way galaxy

- 10^170 is a theoretical number so large that we cannot comprehend it

The key take-away here is that Go can be an incredibly complex game and in order to master it you need a human player or a computer system capable of churning through all this complexity. It is therefore a problem worth solving in the domain of AI.

The Creative Move 37

AlphaGo made a move that media later named Move 37. I am not going to pretend that I understand the mechanics of the move, but what I do know is that media and Go community first saw it as a mistake and then, shortly after, realised it was creative. Lee Sedol himself said that it was “really creative and beautiful”. This takes us to my first question.

What is Creativity?

Let’s try defining what creativity means before exploring the subject further. The word stems from the Latin creare, which means to create or make.

Would you say that the following are examples of creativity?

- A child drawing lines and shapes with a marker pen on a wall

- A cook experimenting with new flavours in a dish

- A musician composing a new melody on the piano

- A gardener arranging a colourful flower bed in a memory of a loved one

- Army general devising a new battle strategy to gain advantage over their enemy

All of the above are creative according to our definition. Assuming we are in agreement here, then we can suggest that creativity doesn’t have to be useful, unique, or good.

How about Darwinism? The evolution of species through natural selection. Is that creative too? If it is, then surely everything that stems from it is also by default creative? I think Darwinism is a great example of creativity, and therefore I would like to revise the above statement.

Creativity doesn’t have to be useful, unique, good or owned by humans.

Creative Duopoly

This might be a tough pill to swallow for many (especially Lee Sedol), but I think this is exactly why Move 37 was dubbed as creative. We, humans, got used to being on top of both the food chain and the creativity ladder. With the rise of AI, we will have to accept the fact that we no longer have a monopoly on creativity and that AI will excel in creativity far beyond our current capabilities.

Reflections

I wrote this post because I couldn’t explain how I felt about Lee Sedol losing to an AI model. I also didn’t know what to think about the impact of AI on my line of work and my hobbies.

Lee Sedol went through a “baptism by fire.” His whole world got turned upside down within two hours, and he did incredibly well not giving up and embracing the challenge. My view is that we should live our lives to the fullest and get to the end full of wisdom and covered with scars of rich and full life. Therefore, I hope he sees this experience as both a blessing and a curse from which he grows as a person.

What about the impact on my line of work and my hobbies? This was a massive wake-up call for me. I would hate to find myself in Lee Sedol’s position, suddenly realizing that my skill is no longer unique or in demand and can now be replaced by an AI model. Upon realizing this, I have embraced AI fully and am excited about what the future holds.

How about hobbies? I do my hobbies because I love the learning process and the state of flow - not the result, so I’m not at all worried about AI and how it might impact my hobbies. If anything, I might ask it to help me compose new music mixing styles of Ludovico Einaudi and Hans Zimmer.

Posts

-

Behaviour Models - Staying on the Right Side of Action Curve

-

Elon Musk by Walter Isaacson - What Did I Learn?

-

AlphaGo - Creative Approach to Winning in an Ancient Game of Go

subscribe via RSS